By Moisés Agosto-Rosario, Director of Treatment

NMAC and its Strong and Healthy Program is thrilled to introduce the HIV 50+ community to the National HIV and Aging Advocacy Network (NHAAN) to commemorate the National HIV/AIDS and Aging Awareness Day. NHAAN is a network of individuals advocating for our collective and cumulative interests as persons aging with HIV. For the past year, a group of NMAC’s HIV 50+ scholars has been creating NHAAN to build a strong network of HIV 50+ advocates on the foundation established by the Denver Principles and MIPA. The Network’s vision is to envision a world in which all people thrive as they age with HIV: Physically, socially, financially, spiritually, emotionally, and in all aspects of their lives.

NMAC and its Strong and Healthy Program is thrilled to introduce the HIV 50+ community to the National HIV and Aging Advocacy Network (NHAAN) to commemorate the National HIV/AIDS and Aging Awareness Day. NHAAN is a network of individuals advocating for our collective and cumulative interests as persons aging with HIV. For the past year, a group of NMAC’s HIV 50+ scholars has been creating NHAAN to build a strong network of HIV 50+ advocates on the foundation established by the Denver Principles and MIPA. The Network’s vision is to envision a world in which all people thrive as they age with HIV: Physically, socially, financially, spiritually, emotionally, and in all aspects of their lives.

The formation of this new Network is crucial to advance the aging and HIV advocacy agenda. There are a significant number of issues that need attention. First, we need biomedical research to understand better the biology of aging with HIV. Second, we need to upgrade the regular medical care and psychosocial services for HIV+ people to respond to the needs of those HIV 50+. Same with mental health, substance abuse, and other social determinants of health. Aging and HIV have a prominent place in NMAC’s policy agenda. In this article, we want to share with our constituent HIV 50+ some of our analysis and strategy.

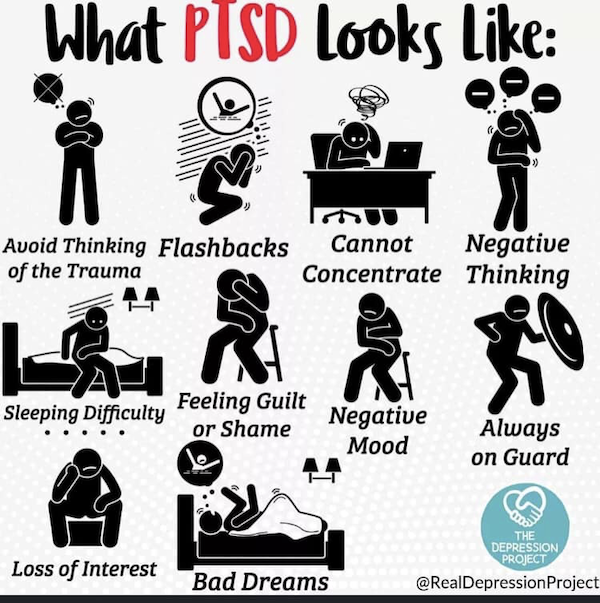

Due to the development of effective antiretroviral treatment and the improvement of HIV care, the life expectancy of people living with HIV (PLWH) has dramatically improved. In the United States, from 2014 through 2018, the most significant percentage increase (51%) in the rate of persons living with diagnosed HIV infection was among persons aged 65 years and older (Center for Disease Control, HIV Surveillance Report, 2018). Of the 1.4 million PLWH in the United States, 50% are fifty years of age and older. By 2030, PLWH 50 years and older will constitute 70% of the individuals living with HIV in the U.S. (WING E. J.,2017, p.128/131-144). This group comprises the first cohort of people living with HIV; long-term survivors and aging over 50. While the life span improves, other non-AIDS-related comorbidities persist in PLWH (Schouten J, 2014;59(12):1787-1797). Social isolation and post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD) are an increasing problem among PLWH over 50. It interferes with their ability to rebuild social networks, adhere to HIV medicine, risk HIV transmissibility, and find the healthcare and psychosocial services they need (Foley L, 2021 Sep 2;11).

A cross-functional approach to long-term medical care and assistance is required. The health systems built to address the needs of PLWH in the United States are not prepared to adequately care for those aging with HIV. It is crucial to integrate HIV and geriatric care. Early screening for comorbidities and prevention protocols of healthy living are necessary to ensure health, quality of life, and longevity among PLWH at age 50 and over. Integrated health and social services should respond to the changing physical, psychological and social needs of PLWH over 50 who need to use HIV and non-HIV services (Autenrieth CS, 2018).

Clinical data suggest that aging with HIV will become a significant public health challenge to address at the federal, state, and local levels. The basic standard of care for PLWH needs to be able to care for the elder by managing HIV infection, prevent and monitor early and multi-morbidity. Today, caring for PLWH consists of controlling HIV replication and lower it to undetectable levels. Viral suppression allows for increased CD4 cells to normal levels and restoring the person’s ability to fight opportunistic infections (Deeks SG, 2015 Oct 1;1:15035). However, viral suppression is only one aspect among other critical issues in the long-term care of those aging with HIV. The HIV + community lives with long-term immune activation due to the constant viral replication inside the HIV latent viral reservoirs in the body (Dufour C, 2020 Jul 1;130(7):3381-3390). The body reacts to the continuous presence of HIV by producing proteins that cause chronic inflammation, which potentially damages organ tissue (Deeks SG, 2013 Oct 17;39(4):633-45).

This immune response plays a crucial role in the aging process of PLWH, resulting in premature aging-related comorbidities (WING E. J.,2017, p.128/131-144). Therefore, even with a well-controlled HIV viral load, PLWH presents age-related conditions seen in their 15 years older HIV-negative counterparts (Willig AL, 2014 Mar;11(1):35-44). Therefore, essential stakeholders are to be part of ensuring the comprehensive provision of services. The stakeholders are HIV 50+ advocates, the U.S. Congress, the Office of National AIDS Policy (ONAP), the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the Health and Human Services (HHS) Administration on Aging, the National Council on Aging (NCOA), the Center for Disease Control (CDC), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), private health insurance, the pharmaceutical industry and the Veteran Affairs (V.A.).

Policy actions to consider are modernizing the Ryan White Care Act, prioritizing and funding research on HIV and aging, providing capacity building on HIV-related services to the Area Agencies on Aging (Federal Agency on Aging) HHS.

Modernization/Reauthorization of the Ryan White Care Act

Congress first enacted this legislation in 1990 as the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resource Emergency (CARE) Act. Legislators amended and reauthorized the CARE Act four times in 1996, 2000, 2006, and 2009. The Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program (RWHAP) legislation has been amended with each reauthorization to accommodate new and emerging needs. The implementation of the Ryan White Care Act is the responsibility of the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). The Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program is the most extensive federal program focused on providing a comprehensive system of HIV primary medical care, essential support services, and medications to low-income people living with HIV who are uninsured or underserved. Ryan White programs are “payer of last resort,” which fund treatment when no other resources are available. This legislation provides grants to cities/counties, states, and local community-based organizations. Over the last three decades, The Care Act has played a critical role in the United States’ public health response to HIV. What was once fatal is now a manageable, chronic condition. In 2019, 88.1% of Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program clients had suppressed viral load, exceeding the national average of 64.7 %. Thus, the RWHAP proves to be essential for the care and well-being of PLWH. Modernization of the Ryan White Care Act is vital to serve the HIV+ elder population’s increasing population adequately. We could argue that if we modernize the RWHAP, elders living with HIV will receive the correct medical care if comorbidities present earlier when they still do not qualify for Medicare. We see diagnoses of non-HIV comorbidities early in their 40’s and ’50s, twenty to ten years before they are eligible for Medicare. Instead of creating a new and costly health system to take care of this population, Congress can reauthorize the CARE Act to accommodate new and emerging needs for the HIV+ elders. With a reauthorization, the RWHAP can be modernized to integrate HIV and geriatric care services that will potentially impact the QOL and lifespan of PLWH.

Prioritize and fund research on HIV and aging.

The NIH’s Office of AIDS research develops a comprehensive HIV/AIDS research plan and established priorities. In addition, it ensures a fair distribution of AIDS research funding through the institutes, making sure the goals and priorities of the research plan are the guiding principles of AIDS research across institutes. This way, duplication of efforts is avoided, fostering collaboration and new research. Because today’s HIV elders represent the first cohort of PLWH aging, Congress should invest in HIV research to better understand the biology of HIV aging. For example, suppose we better understand the role of inflammation in early aging. In that case, we might figure out a way to treat the inflammation mitigating early development of non-HIV comorbidities, impacting QOL and life span. In addition, there will be a return of investment as the cost of treating these conditions will be more expensive than preventing them with early screening, treatment, and preventive care.

Collaboration between HRSA’s HIV AIDS Bureau (HAB) and the HHS Administration on Aging

Congress passed the Older Americans Act (OAA) in 1965 to resolve community social services for older persons. The legislation established authority for grants to states for community planning and social services, research and development projects, and personnel training in the field of aging. Today, the OAA is a significant vehicle for the organization and delivery of social and nutrition services to this group and their caregivers. Under this legislation, HIV+ elders, people with cancer, and other chronic conditions benefit from the essential programs and services offered through the states and the Network of area agencies. The OAA also includes community service employment for low-income older Americans, training, research, and demonstration activities in the field of aging, and vulnerable elder rights protection activities. Collaboration between HRSA and the HHS Administration on Aging on specific HIV services and capacity building can offer providers in the area agencies on aging an understanding of the particularities of HIV services for the HIV+ elder. This collaboration might foster better QOL and have an impact on lifespan. This collaborative approach is a cost-effective way to maximize the resources and services already funded.

In conclusion, these are only some of the actions we can take that will significantly impact the elder living with HIV. Therefore, as a community, we are to be intentional in our efforts and facilitate the engagement and direct participation of the HIV 50+ in all advocacy affairs about improving the health and quality of life of the elder living with HIV.

References

Autenrieth CS, Beck EJ, Stelzle D, Mallouris C, Mahy M, Ghys P (2018) Global and regional trends of people living with HIV aged 50 and over: Estimates and projections for 2000–2020. PLOS ONE 13(11): e0207005. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207005

Cahill, S., & Valadéz, R. (2013). Growing older with HIV/AIDS: new public health challenges. American journal of public health, 103(3), e7–e15. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301161

Cantor MH, Brennan M. (2000) Social Care of the Elderly: The Effects of Ethnicity, Class, and Culture. New York, NY: Springer.

Capeau J. (2011). Premature Aging and Premature Age-Related Comorbidities in HIV-Infected Patients: Facts and Hypotheses. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, 53(11), 1127–1129. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cir628

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2018; vol.31. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published May 2020. Accessed June 5, 2021.

Charles A. Emlet, Ph.D., ACSW, Shakima Tozay, MSW, Victoria H. Raveis, Ph.D., (2011) “I’m Not Going to Die from the AIDS”: Resilience in Aging with HIV Disease, The Gerontologist, Volume 51, Issue 1, February 2011, Pages 101–111, https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnq060

Deeks SG, Overbaugh J, Phillips A, Buchbinder S. HIV infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015 Oct 1;1:15035. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.35. PMID: 27188527.

Deeks SG, Tracy R, Douek DC. Systemic effects of inflammation on health during chronic HIV infection. Immunity. 2013 Oct 17;39(4):633-45. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.001. PMID: 24138880; PMCID: PMC4012895.

Dufour C, Gantner P, Fromentin R, Chomont N. The multifaceted nature of HIV latency. J Clin Invest. 2020 Jul 1;130(7):3381-3390. doi: 10.1172/JCI136227. PMID: 32609095; PMCID: PMC7324199.

Emlet CA. An examination of the social networks and social isolation in older and younger adults living with HIV/AIDS. Health Soc Work. 2006;31(4):299–308 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Foley L, Larkin J, Lombard-Vance R, Murphy AW, Hynes L, Galvin E, Molloy GJ. Prevalence and predictors of medication non-adherence among people living with multi-morbidity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021 Sep 2;11(9):e044987. doi: 10.1136/BMJ open-2020-044987. PMID: 34475141.

Levy, M. E., Greenberg, A. E., Hart, R., Powers Happ, L., Hadigan, C., Castel, A., & D.C. Cohort Executive Committee (2017). High burden of metabolic comorbidities in a citywide cohort of HIV outpatients: evolving health care needs of people aging with HIV in Washington, DC. HIV medicine, 18(10), 724–735. https://doi.org/10.1111/hiv.12516

McMillan, J. M., Krentz, H., Gill, M. J., & Hogan, D. B. (2018). Managing HIV infection in patients older than 50 years. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 190(42), E1253–E1258. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.171409.

Mullings L, Schulz AJ. (2006) Intersectionality and health: an introduction. In: Schulz AJ, Mullings L, editors. Gender, race, class, & health: intersectional approaches. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2006.

Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/inline-files/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf.

Schouten J, Wit FW, Stolte IG, et al. (2014) Cross-sectional comparison of the prevalence of age-associated comorbidities and their risk factors between HIV-infected and uninfected individuals: the AGEHIV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(12):1787-1797.

Warren-Jeanpiere, L., Dillaway, H., Hamilton, P., Young, M., & Goparaju, L. (2017). Life begins at 60: Identifying the social support needs of African American women aging with HIV. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved, 28(1), 389–405. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2017.0030

Watkins, C.C., Treisman, G.J. (2012) Neuropsychiatric complications of aging with HIV. J. Neurovirol. 18, 277–290 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13365-012-0108-z

Willig AL, Overton ET. Metabolic consequences of HIV: pathogenic insights. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2014 Mar;11(1):35-44. doi: 10.1007/s11904-013-0191-7. PMID: 24390642.

WING E. J. (2017). The Aging Population with HIV Infection. Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association, 128, 131–144

Last year White America woke to the over policing of Black people through the killing of George Floyd and too many others to name. What happens when something is unfair to People of Color but needed in White communities? This is the paradigm shift that America is working to answer. In our fight to end HIV, PrEP users are 75% White, yet the majority of people living with HIV and the majority of new cases of HIV are among people of color. PrEP is reaching Gay White men, but not Gay Black men. What does that mean?

Last year White America woke to the over policing of Black people through the killing of George Floyd and too many others to name. What happens when something is unfair to People of Color but needed in White communities? This is the paradigm shift that America is working to answer. In our fight to end HIV, PrEP users are 75% White, yet the majority of people living with HIV and the majority of new cases of HIV are among people of color. PrEP is reaching Gay White men, but not Gay Black men. What does that mean? To my White friends, here is how I navigate these challenges. As an old fem Asian cisgender Gay man and the Executive Director of the agency formerly known as the National Minority AIDS Council, I am professionally aware of the privileges and discrimination that goes with how I present myself to the world. Part of my job is to hold-up communities that are often overlooked or undervalued. Most of my job is to listen and learn from those communities.

To my White friends, here is how I navigate these challenges. As an old fem Asian cisgender Gay man and the Executive Director of the agency formerly known as the National Minority AIDS Council, I am professionally aware of the privileges and discrimination that goes with how I present myself to the world. Part of my job is to hold-up communities that are often overlooked or undervalued. Most of my job is to listen and learn from those communities. Privilege is taking all the oxygen out of the room. I purposely use my privilege in rooms full of White people. I want them to understand that they are not the only important voices. It took me a long time to get comfortable, some would say too comfortable, with this privilege. As an Asian man, it was not something that came naturally. In the world of HIV, it is a very important skill. It is difficult if not impossible for many of you to understand what it means to present as White, yet it is something that every person of color intimately knows. Our value depends on how we present ourselves in the world. The closer we show up as white heterosexual men the better. For most of us that is impossible, yet that is the gold standard for power and wealth in America.

Privilege is taking all the oxygen out of the room. I purposely use my privilege in rooms full of White people. I want them to understand that they are not the only important voices. It took me a long time to get comfortable, some would say too comfortable, with this privilege. As an Asian man, it was not something that came naturally. In the world of HIV, it is a very important skill. It is difficult if not impossible for many of you to understand what it means to present as White, yet it is something that every person of color intimately knows. Our value depends on how we present ourselves in the world. The closer we show up as white heterosexual men the better. For most of us that is impossible, yet that is the gold standard for power and wealth in America. COVID, Black Lives Matter, the Jan. 6 insurrection, and climate change have forced a reckoning. We can probably end the HIV epidemic in the White community by 2030, but if we stay on the same course, I have real doubts about ending HIV in communities of color. This is my pledge to the HIV movement: what is fair cannot be based on White privilege. Our work must embrace the challenge of what is fair to communities who have lived under generations of discrimination and oppression. This is bigger than change; it is a shift in the paradigm. Ending the HIV epidemic in America starts by re-looking at what is fair.

COVID, Black Lives Matter, the Jan. 6 insurrection, and climate change have forced a reckoning. We can probably end the HIV epidemic in the White community by 2030, but if we stay on the same course, I have real doubts about ending HIV in communities of color. This is my pledge to the HIV movement: what is fair cannot be based on White privilege. Our work must embrace the challenge of what is fair to communities who have lived under generations of discrimination and oppression. This is bigger than change; it is a shift in the paradigm. Ending the HIV epidemic in America starts by re-looking at what is fair.